A Folk Horror Crash Course

A brief exploration of folk horror's motifs, history and recent revival for those both new and well-versed!

What could Yellowjackets, Florence + The Machine’s upcoming album Everybody Scream, and the Christmas special of Detectorists possibly have in common? Beyond release dates within the last five years, each seems to indicate something of folk horror’s trickle down into more mainstream media. No longer, it seems, is the genre confined to art house production companies and dusty library corners. Together, these contemporary examples signal a growing appetite for this brilliant genre, as old rural dread seeps quietly back into the mainstream.

Certainly for many, curiosity may have been piqued in recent years with the sudden upsurge of folky films released in quick succession through the late 2010s to now. Of course, Midsommar, Ari Aster’s 2019 cult favourite (quite literally) offered a refreshed example of classic folk horror trope; and of course we cannot forget Robert Egger’s stomach-churning puritanical horror The VVitch (2015). Despite this recent interest, folk horror is a pot that has been bubbling away for arguably over a century, boiling over every few decades with examples that seem to find contemporary audiences when they are needed most. As a folklorist and folk horror obsessive, I am delighted (if a little gatekeepy) for the rekindling of such a nuanced, earthy terror throughout recent media. This article features a crash course in the parameters of genre, the history of folk horror and some modern examples before finally exploring the reason why we are seeing such a resurgence recently. If I can get even one of you to fall down this wonderful rabbit hole, I have done my job and done it well.

What is Folk Horror? : Generic Parameters

Folk horror unsurprisingly does exactly what it says on the tin: it combines elements of folk tradition and classic horror tropes to create a slower, earthier strain of horror that offers a refreshing departure from its literary-cinematic cousins the slasher or paranormal narrative. Folk horror blends the familiar rhythms of rural life with the creeping sense that something ancient and sinister still lingers just beneath the surface. The ‘horror’ of this genre often simmers quietly—until it doesn’t, exemplifying how dread best operates through slow suggestion before revelation, all our primal fears bursting through once-still soil. I could very easily get ahead of myself here, as I am so excited to share some of my favourite examples but I cannot rightly continue this article without offering some brief insight into the generic parameters and motifs that define folk horror.

In its simplest terms, a typical folk horror narrative can be boiled down to a few recurrent tropes. Though this approach to generic dissection may appear pretty formulaic, identifying the typical tropic patterns of the genre allows us to see just how far folk horrors roots have reached today in the more subtle employment of the aesthetic in unexpected places.

Here are some classic tropes to look out for:

1: Isolation and Rurality

When we think of folk horror, we seldom envisage the urban or inhabited. It is no wonder folk horror is most at home amongst sweeping moors, dense forests or desolate marshland when the very heartbeat of the genre is isolation. A windswept hillside or remote village does more than simply provide aesthetic appeal, it offers the cultural and psychological separation from modernity required for various terrors to unfold relatively uninhibited.

In these places time moves differently, the rules of the outside world lose their grip and older, stranger systems of belief and governance take over. For the protagonist isolation strips away safety and certainty. There’s no help coming, no phone signal, no authority to appeal to. The deeper they travel into the countryside, the deeper the descend into a half-forgotten past. In folk horror, isolation isn’t just a setting but a spell. It removes the characters from everything familiar, forcing them into a world that still remembers the old gods, and still demands their due. The fens can’t help you, they can only reflect your cries back to you.

2: The Outsider

So who’s cries are we hearing? The outsider is the audience’s mirror in folk horror, they are the rational intruder stepping unknowingly into a world ruled by older laws. They’re often a scholar, a policeman, a researcher; stereotypically someone who believes the world is explainable, that superstition is a relic. But the countryside they enter doesn’t obey the same logic.

The outsider arrives seeking order and instead finds ritual, belief, and secrecy. Their presence disturbs a balance they don’t understand, and their refusal, or indeed, inability to adapt becomes their undoing. The trope works because it plays on a deep cultural anxiety: the divide between the urban and the rural, the modern and the ancient. The outsider is an apt conduit for the reader or viewer who might assume the old world is gone. Folk horror punishes that arrogance. By the end, the outsider either vanishes into the landscape or becomes part of it, absorbed into the very system they came to expose. Escape is a rare thing and throughout folk horror, no one walks away unchanged.

3: The Community

At the centre of folk horror lies the community, not as a collection of individuals but as a single living organism bound by tradition, secrecy, and shared devotion. This community is often simultaneously alluring and menacing. There is that coveted offer of belonging, but at a cost. This pocket society embodies a worldview untouched by modern scepticism, where ritual is not performance but a necessary maintenance of interpersonal ties. To an outsider, their unity feels alien, a collective mind speaking with one voice, unmoved by logic or morality as we understand it. This community is not always closed off and hostile, in fact oftentimes we see the outsider welcomed with suspiciously open arms, fed and tended to until the day of their inevitable demise.

In these stories, the community becomes the vessel of the past. It holds memory, faith, and the knowledge of what the land demands. Whether it is a rural village, an isolated island, or a hidden cult, the community preserves what the modern world has tried to bury. Their calm hospitality conceals the weight of history, and their smiles hide the inevitability of sacrifice. The question is what happens when civilisation’s values are turned on their head? The answer is rarely survival.

4: The Ritual

Strange rituals and practices abound throughout folk horror, usually focused around the land, the seasons and the something lurking just beyond the borders of comprehension. These practices can be small and subtle, like seasonal offerings or whispered prayers, or they can be dramatic and violent, demanding blood or sacrifice. In every case, the ritual carries weight. It is not optional and it is not symbolic in the way outsiders might assume. To those who follow it, the ritual is a necessity, a guarantee that the world remains in balance.

For the outsider, the ritual is often terrifying. It exposes the limits of reason and challenges the notion that humanity controls its own destiny. It can be the culmination of slow-building dread, the moment when the quiet unease of the countryside becomes undeniable. Folk horror relies on the tension between participation and observation. Witnessing a ritual from the outside is dangerous, but joining it carries consequences that the modern mind may never anticipate.

Folk Horror’s Heritage

Folk horror actually emerges earlier than most often assume from the cultural tumult of the Fin-de-Siecle —the concluding years of the nineteenth century. This period saw a profound amount of cultural anxiety making it an ideal breeding ground for the burgeoning genre. As the nineteenth century drew to a close, industrialisation and urbanisation were reshaping daily life, displacing communities and eroding traditional ways of living. At the same time, there was a fascination with the occult, ancient paganism, and the unseen forces lurking beneath modernity. Writers and artists of the era were preoccupied with the tension between progress and tradition, reason and superstition, civilisation and the wild unknown. The progenitors of proto-folk horror appeared to take the aesthetics of Pastoralism that captured the imaginations of writers such as Morris, Swinburne and Clare and created a warped kind of reflection that countered the prevailing view of the land as harmonious and welcoming. For these contrarians, livestock ailed and died, crops failed and the fields and forests appeared eerily silent. No longer were we welcomed by the land, in fact, it seemed often that the land was fighting back.

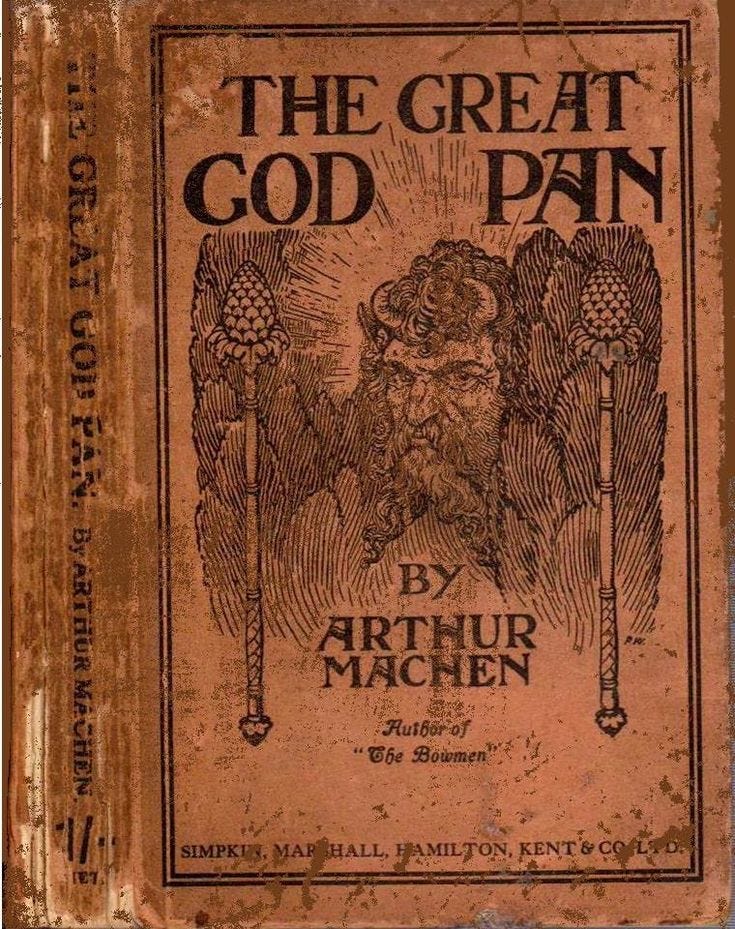

Writers such as Algernon Blackwood, E.F Benson, M.R James and Arthur Machen excel at this decadent anti-pastoralism. Indeed, though these writers still regard the countryside as something sacred, by no means is it benevolent and why should it be when we are consistently scarring and scorching it? If you are looking to start your folk horror journey right at the roots, I cannot recommend enough Machen’s seminal work The Great God Pan (1894). Though Machen seems to have faded into some canonical obscurity over the years, he can arguably be credited with the very genesis of the genre with this short generic hybrid of science fiction, warped pastoralism and monster tale. The narrative explores themes of forbidden knowledge, the persistence of ancient pagan powers, and the fragile boundary between civilisation and the primal natural world. Though his name is infrequently invoked today, a read of the novella will illuminate just how far Machen’s influence stretches throughout horror in general with his oeuvre acting as a highly valued cornerstone for authors from H.P Lovecraft to Stephen King.

Though the essence of folk horror had been bubbling away for some time, the genre as we know it today only really found its more modern shape in the late 60s and early 70s with its entrance into cinema. A period marked by social experimentation, free love, and a renewed fascination with our rural past bought the genre into sharp focus as a response to this shifting cultural landscape. Three films are often cited as the genre’s ‘Unholy Trinity’: Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), and The Wicker Man (1973). Witchfinder General explores historical persecution and moral collapse in a rural village, while The Blood on Satan’s Claw evokes the supernatural and satanic forces lurking beneath the countryside. The Wicker Man remains the most iconic, portraying an outsider’s confrontation with a tightly knit pagan community whose rituals mask deadly truths. Beyond this core of classic narratives I also recommend the brilliantly unsettling Penda’s Fen for more abstract, dreamlike experimentation that focuses directly on the clash of paganism and Protestantism. Further I always suggest trying out The Blair Witch Project for some eerie insight into how folk horror developed a little differently across the pond.

Why a 21st Century Revival?

Folk horror has returned to prominence in the twenty-first century, and its resurgence feels less like nostalgia and more like recognition. The genre speaks directly to the anxieties of the present moment: the disintegration of community, the alienation of modern life, and the uneasy sense that the systems meant to protect us are fraying at the edges. In a world increasingly defined by technology, ecological collapse, and political uncertainty, folk horror offers a confrontation with something older and more elemental. It reminds audiences that the land has memory, and that progress often hides what it has buried.

Contemporary films such as The VVitch (2015), Midsommar (2019), Men (2022), and Enys Men (2022) revisit the traditional motifs of the genre—ritual, isolation, and odd community structures—but reframe them for a modern context. The rural setting now feels not only remote but timeless, detached from global modernity yet somehow charged with its consequences. The outsider is no longer merely a curious visitor from the city but often a figure searching for meaning in a disenchanted world. The old gods have returned not through religion, but through unease, trauma, and ecological despair.

This revival can also be seen as part of a broader cultural movement toward re-enchantment: a growing desire to recover mystery and meaning in an age dominated by data and rationalism. Folk horror offers that possibility, but never safely. It lures us with beauty, tradition, and belonging, only to reveal the violence and sacrifice beneath them. The rituals in modern folk horror are not only about appeasing ancient forces; they are about exposing what must be given up to sustain the illusion of order. The genre’s new wave also resonates with contemporary environmental fears. As climate change and ecological degradation accelerate, the idea that nature might take revenge, or that humanity might be forced to reckon with its neglect of the natural world feels increasingly plausible. Folk horror gives that reckoning a mythic shape.

Ultimately, the revival of folk horror is a return of the repressed. The same cultural currents that once gave rise to the proto-genre in the late Victorian period— disenchantment, technological upheaval, and loss of faith—are alive again today. Just as Arthur Machen wrote of ancient gods stirring beneath the surface of Welsh fens and forests, contemporary storytellers are sensing old energies awakening beneath the digital world. Folk horror thrives in moments of uncertainty, when the future feels fragile and the past refuses to stay buried. That is why it has returned now, and why it feels more potent than ever.

Recommended Reading:

The Great God Pan – Arthur Machen (1894)

Ghost Stories of an Antiquary – M.R. James (1904)

Witch Wood – John Buchan (1927)

Cold Hand in Mine – Robert Aickman (1975)

The Ritual – Adam Nevill (2011)

Starve Acre – Andrew Michael Hurley (2019)

The Lamb – Lucy Rose (2025)

Recommended Viewing:

Witchfinder General (1968)

The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971)

The Wicker Man (1973)

Penda’s Fen (1974)

The Blair Witch Project (1999)

The VVitch (2015)

Midsommar (2019)

Men (2022)

Enys Men (2022)

Brits of a certain age tend to get misty-eyed about Children of the Stones, a mini-series (for children!) From the 1970's.

It is extremely seventies, and completely folk-horror.

I'll link to it here with the observation that kids' tv since has expected much less of its audience...

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLDn4jNKfVvvg_xmgLqzgY7h84_nWje4Mx&si=EMnQZ3wBkHX4xH2h

I will also add Cunning Folk, also by Adam Nevill! I read it this year and it was excellent. Very spooky and an excellent folk horror.

one of my favourite documentaries is Woodland Dark, which is a documentary about cinematic folk horror. HIGHLY recommend. it’s on Shudder and Youtube (for rent).